The Tijâniya is the largest of Senegal’s Sufi orders in terms of number of affiliates but the order is subdivided into several distinct branches, each independent of the other. Within certain branches too there are important internal divisions.This fractured political and administrative structure explains the large number and diversity of Tijânî shrines and settlements in Senegal.

The principal branches of the Tijâniyya in Senegal are:

- The most important of the Tijâni branches, at the national level, is the Sy Zâwiya based in Tivaouane. Established there in 1902 by El-Hadj Malik Sy (1855-1922), this branch was the first to organize zâwiyas in the emerging colonial towns, in the capital cities: Saint Louis and Dakar, as well as in the main rail escales.

- At the international scale, the most active Senegalese branch of the Tijâniya is Al-Tarbiyya, established in Kaolack’s Madina Baye neighborhood by El-Hadj Ibrahima Niass (1900-1975) in the 1930s. Its network of zâwiyas extends across West Africa (the Gambia, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria) and to the US.

- Also in the 1930’s Tierno Mamadou Seydou Baa (1898-1980), a Tijânî sheikh from the Fuuta Tooro, established his branch of the order in Madina Gounass, in the Upper Casamance.

- The Mahdiyya branch of the Tijâniyya was established in Tiénaba in 1882 by Amari Ndack Seck (1830-1899).

- The Senegalese branch of the Umarian Tijâniya, established by El-Hadj ‘Umar Tall (1797-1864), is based in Dakar. It owes its presence in the capital to the career of El-Hadj Tierno Sydou Nourou Tall (1862-1980).

Senegal’s Tijâni shrines come in two types. There are urban zâwiyas which generate entire Sufi neighborhoods (i.e. Hadji Malik neighborhood in Tivaouane, Madina Baye neighborhood in Kaolack), and there are rural settlements such as Taïba Niassène, Tiénaba and Fass in Mbacol, which are akin to the Murid shrine towns discussed on the previous pages. All the places described in this and sister pages can be viewed by downloading this Google Earth (kmz) file.

Tivaouane

Tivaouane (pop. 40,000) is an important center for the Tijâniya order. Al-Hâjj Malik Sy (1855-1922), already an leading Tijânî master, elected to settled in the town with his family and students in 1902. At that time, it was a bustling little colonial trading center and railroad town (called an escale in French), important to the peanut cash-crop economy. The area had already attracted another Sufi sheikh, Cheikh Bouh Kounta (1844-1914), who established his Qâdirî order in Ndiassane, about 4 km south of Tivaouane.

Tivaouane at 1:50 000 scale. The Qâdirî center of Ndiassane lies 4 kilometers to the south. (source: Service Geographique National du Senegal, 1:50 000 ND-28-XIV Thiès 3c, 1991)

Al-Hâjj Malik’s move to Tivaouane was part of a larger initiative to anchor the Tijâniya in Senegal’s emerging colonial urban network. He settled in the “African” or “native” neighborhood, just to the south of the colonial escale, a neighborhood now called Hadji Malik. At the time, escale neighborhoods were reserved for businesses and warehouses, and for the colonial administration (such as it was).

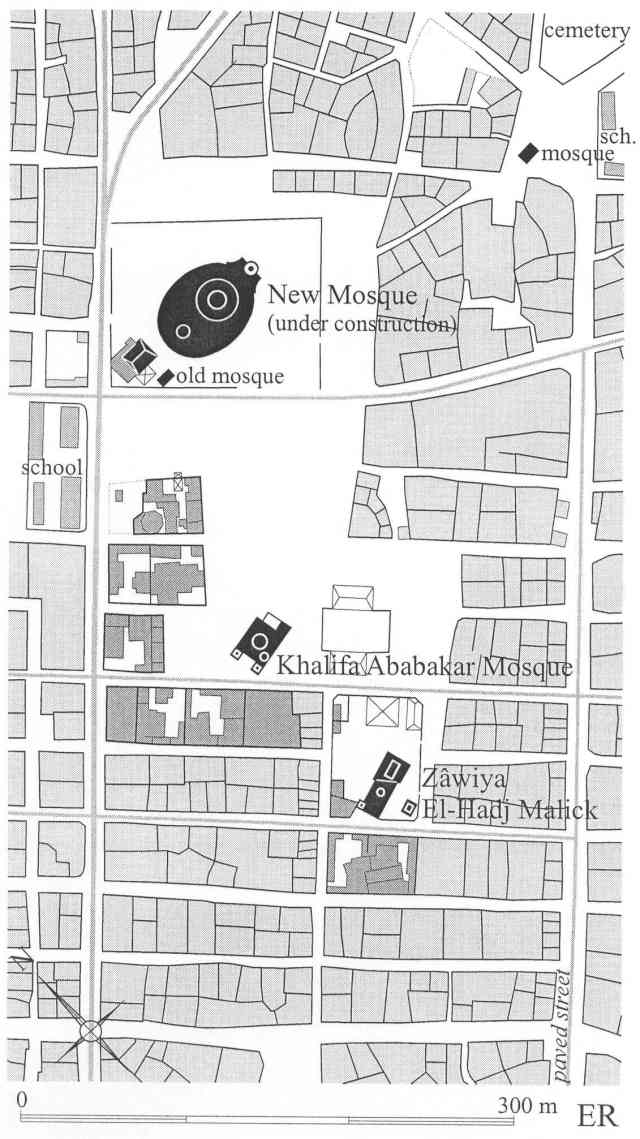

Hadji Malik neighborhood is known for its “three mosques,” all built by the Sy Tijâniyya.

Al-Hâjj Malik Sy built the Tivaouane zâwiya in 1907, across the street from his house. When he died he was buried next to the zâwiya. His son Sëriñ Abdoul Aziz Sy, Caliph of the Sy Tijâniyya from 1957 to 1997, is also buried there.

The Al-Hâjj Malik Sy Zâwiya has one minaret. It has been rebuilt several times since its foundation in 1907. I took the above picture in December 2001. I thank photographer Charles Cecile for sending me a photo of the Zâwiya he took in May 2013. I post it below with his permission (http://www.cecilimages.com/).

Mausoeum of Abdoul Aziz Sy, on the qiblah wall of El Hadj Malik Sy Zâwiya, Tivaouane, May 2013 (ph. © Charles O. Cecil)

In 1922 Al-Hâjj Malik was succeeded by his eldest surviving son, Khalifa Ababacar Sy (1884-1957). When Ababacar died, a new mosque-mausoleum was built for him two blocks away from his father’s initial zâwiya. The building of this second religious monument in the holy neighborhood signaled a deep division within the Sy family and the Sufi order Al-Hâjj Malik had established, a division exacerbated by the heated partisan politics of the independence era.

The Khalifa Ababacar Sy Mosque has two minarets. When I took these photos in 2001 the Mosque still displayed its original architectural motifs. Charles Cecile‘s photo below shows that it has since been overlayed in cut stone and tile-work.

In the 1980s the second Caliph of the Sy Tijâniya, Sëriñ Abdoul Aziz Sy “Dabakh” (1904-1997), began construction of a large Friday Mosque on properties expropriated and demolished for the purpose. He also had many city blocks in the vicinity of the two older religious edifices cleared to make room for open spaces. These are necessary to accommodate the large crowd of pilgrims, over one million strong, which congregates in Tivaouane each year to celebrate the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad (Mawlid al-Nabî), an event called the Gàmmu in Senegal.

The Great Mosque’s oval shape makes best use of a large open space awkwardly oriented vis-a-vis the qibla (ph. Eric Ross)

Satellite image of the new egg-shaped Friday Mosque nearing completion in Tivaouane. North is at the bottom of the image. The qibla direction, to the left, is marked by the Mosque’s single minaret. The older mosque on the site is directly to the right of the new one. (Source: Google Earth)

Tivaouane’s new egg-shaped Friday Mosque with signature drill-bit minaret was begun by Sëriñ Abdoul Aziz Sy and is still under construction. The older mosque on the site, built c. 1900 and tiny in comparison, has been retained on the grounds of the new one. It is one of the few surviving examples of the first generation of masonry mosques in Senegal’s colonial towns.

The first mosque on the site dates from about 1900. Its veranda-type plan is similar in structure to the houses of the neighborhood at that time. (ph. Eric Ross)

The Caliph General of the Sy branch of the Tijâniya today is Sëriñ Mansour Sy.

Saint Louis

Malik Sy first lived in Saint Louis in the 1880s, studying Islamic sciences under its resident masters, and it is to Saint Louis that he returned from the Hajj in 1890. At the time, Saint Louis was one of the “four communes” whose elites enjoyed full French citizenship. It was the capital of the colony of Senegal and of the entire AOF (French West African colonial federation) as well. The city was home to Senegal’s most urban Muslim community.

The administrative district around the “Gouvernance” separates the island city of Saint Louis into a largely Catholic “Sud” and a largely Muslim “Nord.”

Upon returning from hajj, Malik Sy opened a first Tijâni zâwiya in the city’s North Ward (Nord). This first establishment is indicative of the urban orientation he imparted on the branch of the Tijâniya he was to found. Nord was the heart of city’s Muslim community, anchored by the Friday Mosque and the schools of the clerics, some of whom worked for the colonial administration as civil servants. The South Ward (Sud) of the island, on the other hand, was predominantly Catholic, with the church and the Catholic hospital. The politico-administrative center around the “Gouvernance” stood between the two wards.

Dakar

The next urban endeavor, following Al-Hâjj Malick Sy’s definitive establishment in Tivaouane, was to build a zâwiya in Dakar, where the capital of the AOF had just been moved (1902). As in Saint Louis, a site near the center of the city, on what is now Lamine Guèye Avenue, was selected.

At the time the zâwiya was built (1912), this street lay at the heart of Dakar’s “native” quarter. The European quarter, with its administrative institutions lay further east, next to the port and what is now called Place de l’Indépendence. The Friday Mosque on Rue Blanchot marked more or less the division between the two ethnic/racial zones. An outbreak of the plague in 1914 caused the colonial authorities to expel the African population from their neighborhood (a new neighborhood called Medina was established for them about 1.5 km away). The expulsion was never complete and both the Tijâni zâwiya and the older Khadr (Qâdiri) zâwiya remained embedded in the fabric of the enlarged European administrative quarter, designated as the “Plateau,” the heart of French colonial Africa.

Map of part of central Dakar. Both the Tijânî and the Khadr (Qâdirî) zâwiyas occupy corner lots on Lamine Guèye Avenue.

Dakar’s first Friday Mosque, at the corner of Blanchot and Carnot streets, was built in the 1880s. It has been extended and rebuilt several times since. Its imam has always been a Tijânî sheikh.

The second Tijânî monument in Dakar is the mosque-mausoleum of Seydou Nourou Tall (below). Al-Hâjj Tierno Seydou Nourou Tall (1862-1980) had been a disciple of Al-Hâjj Malik Sy and a senior figure in his zâwiya. When he settled in Dakar in the 1920s Tierno Seydou Nourou Tall was not only contributing to his master’s urban vision, he “re-centered” the Umarian Tijâniya of Senegambia, bringing younger members of his Toorodbe family with him to the capital. Famed for his diplomatic skills, he was also a consultant on Islamic affairs for the colonial administration, serving as ambassador-at-large after WWII.

The Mosque of Tierno Seydou Nourou Tall stands at the corner of Avenue El Hadj Malik Sy and Corniche Ouest. (ph. Eric Ross)

The mosque-mausoleum of Seydou Nourou Tall, on the Corniche Ouest in Medina neighborhood, was completed in 2008 (see this post). It is a prominent Islamic monument on this showcase vista of “emerging” Dakar.

Pire Gourey

The town of Pire has a venerable history as a center of Islamic education. It was established by Khâli (qâdî) Amar Fall in the 17th century and thrived as an educational center until French forces destroyed it in 1869.

The town, renamed Pire Gourey, was rebuilt in the 1880s as a rail escale. When Al-Hâjj Malick Sy settled in Tivaouane, 10 km to the southwest, he asked another Tijânî cleric, Al-Hâjj Tafsir Abdou Cissé, to open a school in Pire Gourey. Members of that family still run schools in Pire. I have not yet visited the place.

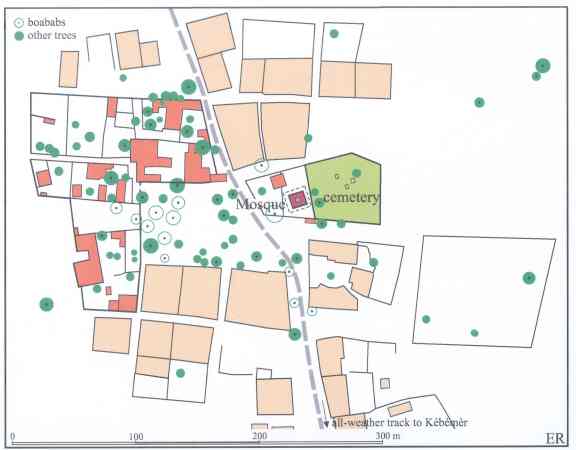

Fass Diacksao, in Saniokhor

The rural settlement of Diaksao, also known as Fass Diacksao, was established by Al-Hâjj Malik Sy some 6 km east of Pire Gourey in the 1890s. It was a center of Islamic instruction but also of peanut cultivation. Located in the booming Peanut Basin, revenues from this estate and others helped finance Al-Hâjj Malik’s urban establishment in near-by Tivaouane.

Fass in Mbacol

The clerical town of Fass, in Mbacol province, was established by a Tijânî sheikh named Sëriñ Tit Cissé Touré in 1894. Fass is named for Fez (Fâs) in Morocco, home to the mother zâwiya of Tijâniya where Sheikh Ahmad al-Tijânî is buried. Sëriñ Cissé Touré’s son, Cheikh Touré (b. 1925) is an influential Senegalese Muslim intellectual. After his studies in Algeria he helped establish the Union Culturelle Musulmane (UCM) in 1953 and the Jama’atou Ibadou Rahman in 1979, Senegal’s principal Islamic reform associations. Cheikh Touré and the reformist movement have been critical of many of the practices of Senegal’s Sufi orders.

Fass, in Mbacol, is known today for the Arabic-language Islamic high school which the Touré manage.

The Tijâniyya zâwiya in Fez, Morocco

Fass (sometimes spelled “Fas”) is a common toponym in Senegal. For over a thousand years the Moroccan city of Fez (Fâs) has played an important role in the dissemination of Islam, and of the Islamic sciences in particular, across the Sahara and Senegambia. Fez is famed for its many scholars, for its Sufi masters and institutions, and for its books. Its reputation in Senegal was greatly enhanced when the Tijâniya order spread there in the second half of the 19th century, hence the plethora of Tijânî placed named “Fass.”

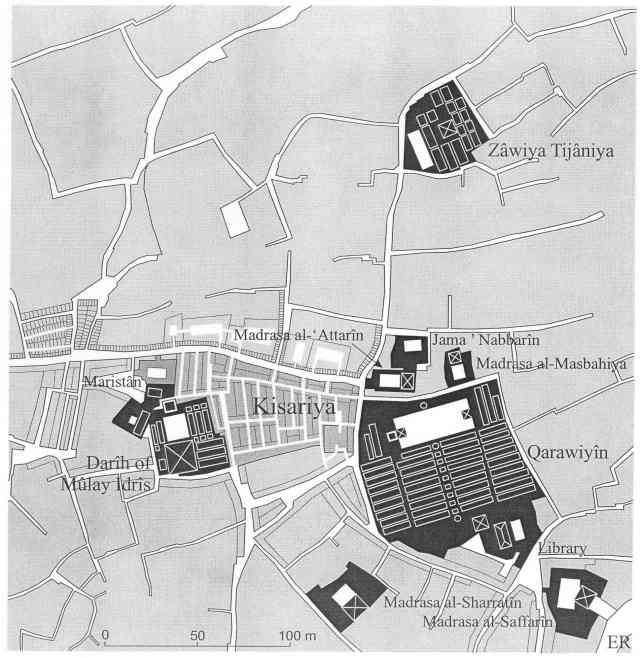

Al-Hâjj Malik Sy’s policy of establishing zâwiyas in the downtown cores of cities appears to be rooted in Tijânî practice. The location of Sidi Ahmad al-Tijânî’s zâwiya in Fez, seat of the international Sufi order, could hardly be more central. It is located 200 m north of the Qayrawiyyin Mosque, close to the city’s commercial heart (the Kisariyya) and to the shrine of Mulay Idris II, the city’s founder and patron saint.

The Qayrawiyyin Mosque is the city’s single most important religious institution and has long been a center of Islamic scholarship. Established by Fatima al-Fihri in 859 CE, it soon developed into an important university. Gerbert d’Aurillac (946-1003), later Pope Sylvester II, was among the Christian students who studied sciences in Arabic at Qayrawiyyin. In the course of the 13thand 14th centuries the Merinides established five royally-endowed madrasas (law schools) in its immediate vicinity.

The Tijânî zâwiya is visited by many pilgrims from West Africa and has recently been beautifully restored, largely thanks to their donations.

Kaolack

Kaolack (pop. 180,000) is home to a major branch of the Tijâniya order, one with a global reach. It became a center for the Tijâniya in 1910, when Al-Hâjj Abdoulaye Niass (1844-1922), already a famous master, settled there with his family and disciples. It was one of his sons, Al-Hâjj Ibrahima Niass (1900-1975), who expanded the order internationally, first across West Africa and then to North America.

It was Al-Hâjj Malik Sy who asked Al-Hâjj Abdoulaye Niass to settle in Kaolack. The move was part of Sy’s policy of investing in the emerging urban centers of colonial Senegal. Kaolack was a booming port city on the Saloum River, connected by rail to a prosperous hinterland in the Peanut Basin. Abdoulaye Niass settle in the city’s Leona neighborhood, where he opened a Tijânî zâwiya. Prior to then, Abdoulaye Niass had been active throughout the Saloum region and the Gambia, then under British control. He had also made several visits to the mother zâwiya of the Tijâniya in Fez and had thus acquired a high degree of legitimacy as a Tijânî sheikh.

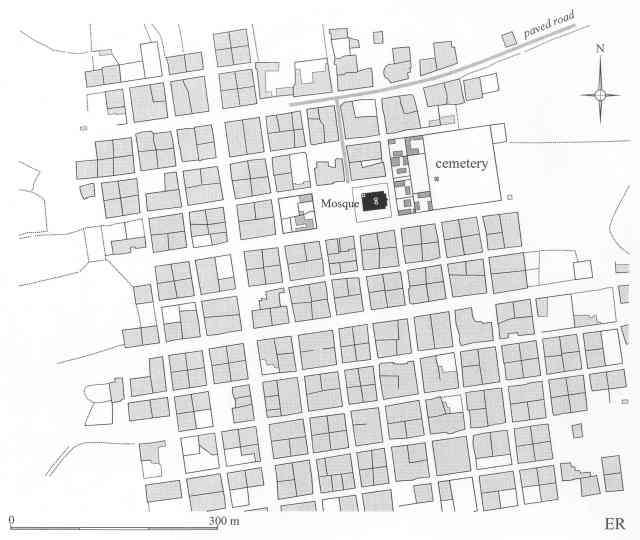

Kaolack at 1:50 000 scale (source: Service Geographique National du Senegal, 1:50 000 ND-28-XIV Thiès 2b, 1991)

When Al-Hâjj Abdoulaye Niass died he was buried in the Leona zâwiya. Authority over his branch of the Tijâniyya passed to his eldest son, Ahmadu Momar Khalifa Niass (d. 1957).

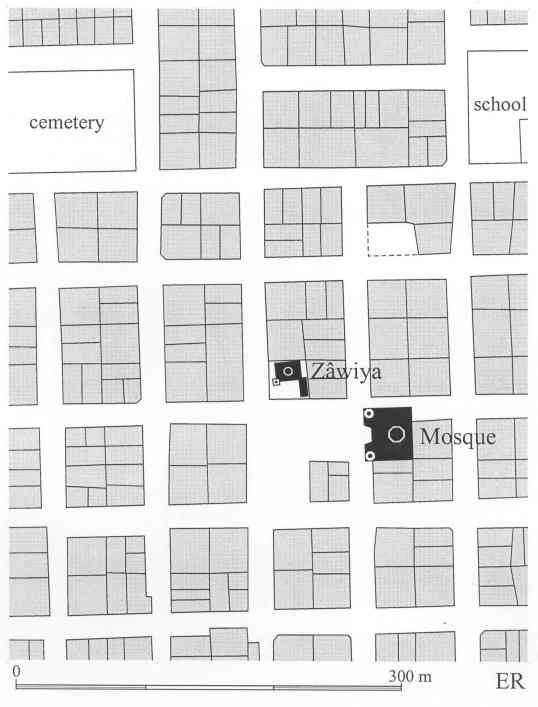

Plan of Leona neighborhood in Kaolack, showing the zâwiya of Al-Hâjj Abdoulaye Niass and the newly enlarged mosque. The houses in front of the zâwiya and the mosque are being demolished to make room for a public square.

In the 1930s another of Abdoulaye Niass’ sons, Al-Hâjj Ibrahima, moved away from his brother’s zâwiya in Leona neighborhood to settle his followers in a new neighborhood he called Madina Baye, allotted along the railroad to the north. Baye Niass (as he is lovingly called) is buried in a mausoleum next to the Mosque.

Today, Madina Baye is one of the Kaolack’s most important neighborhoods. It is dominated by the Great Mosque and is dotted with institutes of religious instruction and numerous Koranic schools. As this Tarbiya branch of the Tijâniya has zâwiyas across West Africa and the US, Madina Baye harbors an international Sufi community.

Mausolem of Al-Hâjj Ibrahima Niass, next to the Madina Baye Mosque. Its green tiled roof and internal stucco-work are Moroccan in style. (ph. Eric Ross}

Since 2010 the Caliph of Baye Niass has been Al-Hâjj Ahmed Tidiane Niass

Taïba Niassène

Prior to moving his family and disciples to Kaolack, Al-Hâjj Abdoulaye Niass’ enterprise had been largely rural. The largest of these rural establishments is Taïba Niassène, where Ibrahima Niass was born c. 1900. Abdoulaye Niass may have founded Taïba in the early 1860s, when he was part of the entourage of the Tijânî jihâdist Maba Diakhou. Taïba Niassène lies 12 km from Nioro, Maba Diakhou’s capital, and is close to the Murid shrine town of Porokhane.

Tiénaba

Tiénaba (also spelled Thiénaba and Cénaba) is a small Tijânî center 12 km east of Thiès. It was established in 1882 by Amary Ndack Seck (1830-1899), one of the leaders of Ahmadu Sheikhu’s ill-fated jihâd of 1871-75. Amary Ndack settled in Tiénaba after the site was revealed to him through a luminous sign in a state of istikhâra (seeking God’s guidance).

The sanctuary of Tiénaba-Seck consists of the Mosque and a cemetery attached to its qibla side. The part of the cemetery closest to the qibla wall is occupied by mausolea of Amary Ndack Seck and his successors. Amary Ndack’s large residence, called Keur-gu Mak, lies across the square from the Mosque, to the west. Since 2008 the Caliph of Tiénaba has been Sëriñ Cheikh Ahmed Tidiane Seck. I have not yet visited Tiénaba.

The Tijânî town of Tiénaba (called Tiénaba Seck) is separated from the government settlement of Tiénaba Gare by the railway. The direct entrance to Tiénaba from National Road #3 is marked by a symbolic gate.

With about 3000 inhabitants, Tiénaba is a very small shrine-town but 37 neighboring villages, inhabited by about 20,000 of the tarîqa‘s affiliates, are under its administration. It has a strong religious identity. The Tijâniya-Mahdiya keeps strict control over the town and its inhabitants, imposing corporal punishment according to its interpretation of the sharî‘a. Since the colonial era Tiénaba has been a de facto special legal zone, able to manage its own affairs with a degree of autonomy. All government institutions are kept at arms length in Tiénaba Gare, located 1 km away along the national road. The railway, built after Amary Ndack Seck had established the center, separates the two, with the sharî‘a on one side of the tracks and the secular state on the other.

Tiénaba Kayor

Amary Ndack Seck was born in another place called Tiénaba, established by his father Massaer Seck in Kayor. The configuration of the mosque and cemetery in Amary Ndack’s Tiénaba (above) resembles that of his father’s original Tiénaba in Kayor.

Madina Gounass

Madina Gounass in Fuladu (Upper Casamance) was founded in 1935 by a Tijâni shaykh named Al-Hâjj Tierno Mamadou Seydou Baa (1898-1980). Tierno Seydou Baa was a Toroodbe cleric from Futa Tooro who had studied in Thilogne. He and a number of his Futanke compatriots went to the Fuladu in order to bring its “wayward” Fulbe inhabitants (Peul or Peulh in French) back to the “Straight Path” of Islam. This mission first brought him to Al-Hâjj Tierno Aliou Thiam’s town of Madina al-Hadji (about 120 km west of Madina Gounass), where he settled in 1927. Seydou Baa married Aliou Thiam’s daughter. After his master’s death he founded his own settlement, called Madina Gounass, where a program of agricultural production and religious instruction was adopted.

Tierno Seydou Baa set out to establish “pure” Islam through strict application of the sharî‘a. Presence at mosque for all canonical prayers is obligatory for all able-bodied adults. Alcohol and tobacco are forbidden, as are all forms of secular entertainment. Corporal punishment is implemented by the city’s religious leaders and, as in Tiénaba, women are veiled in public and their movements are restricted. Women are also excluded from the annual khalwah at Daaka, 9 km east of Madina Gounass. The Daaka is an annual spiritual retreat where men assemble for nine days and nights.

Since the late 1980s, the Madina Gounass Daaka is also celebrated by Halpulaaren Tijânî expatriates (Gounassianke) in the Parisian suburb of Mantes-la-Jolie.

More even than Tiénaba Seck, Madina Gounass has managed to institutionalize its special legal status vis-a-vis the state. In 1978 it aquired the status of an “autonomous rural community,” like Touba. In 2004 the population of the rural community was estimated at 34,488, of which probably 25,000 reside in the town itself.

The 1988 urban master plan for Madina Gounass was drafted by Al-Hâjj Ahmadou Abdoulaye Diagne, civil engineer, civil servant and member of the order. This plan was drafted and implemented under the auspices of the order’s current Caliph, Al-Hâjj Tierno Ahmed Tidiane Baa. The same plan also laid out the grid for the annual tent city at Daaka.

Municipal politics, even of the type permitted within an “autonomous” sharî‘a community under the authority of a Caliph, have proven disastrous for the founder’s original design. Economic cleavages within this Toroodbe class-based society have crystallized somewhat along ethnic lines, with the Futanke monopoly on power being challenged by a Peul underclass with access to new sources of revenue.

The city has become socially and politically divided, and divisions in the fabric of Madina Gounass society have been imprinted on the topography of its center. Less than 200 meters from the main “Toucouleur” (Futanke) Friday Mosque established by Tierno Seydou Baa, there is now a “Peul” (Fulakunda) Friday Mosque. The khalwah at Daaka too now seems to have split into two separate celebrations.

Despite several attempts to do so, I have yet to visit Madina Gounass as it is located in the Upper Casamance, far from the other Sufi centers discussed on these pages. It remains on my “to do” list.

Bibliography on the Tijânis of Senegal

- Bâ, Cheikh (1964), “Un type de conquête pionnière en Haute Casamance : Madina-Gounasse”, thèse de 3e cycle de géographie, Paris, 271 p. (I have never been able to get hold of this study. If anyone has a copy, please let me know.)

- Bousbina, Said (1997), “Al-Hajj Malik Sy : sa chaîne spirituelle dans la Tijaniyya et sa position à l’égard de la présence française au Sénégal”, in Le temps des marabouts : Itinéraires et stratégies islamiques en Afrique occidentale française v. 1880-1960, édité par David Robinson & Jean-Louis Triaud, Karthala, Paris, pp. 181-198.

- Dia, Mamadou (1980), “Une création originale: la communauté de Madina Gunass”, in Islam et civilisation négro-africaines, Nouvelles éditions africaines, Dakar, pp. 127-130.

- Diop, Daouda (2003), “La Tidjannyat Mahdiste de Thiénaba Seck : son implantation et son évolution (1875-1973)”, unpublished Master’s thesis, Département d’histoire, Faculté des lettres et sciences humaines, Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar.

- Gray, Christopher (1988), “The Rise of the Niassene Tijaniyya, 1875 to the Present”, in Islam et sociétés au sud du Sahara, #2, pp. 34-61.

- Hutson, Elaine S. (2001), “Women, Men, and Patriarchal Bargaining in an Islamic Sufi Order: the Tijaniyya in Kano, Nigeria, 1937 to the Present”, in Gender and Society, vol. 15, #5, pp. 734-753.

- Kamara, Cheikh Moussa (1979), “Rapports entre Qâdirites et Tijânites au Fouta Toro aux XIXe et XXe siècles”, in Bulletin de l’IFAN, tome 41, série B, #1, pp. 190-207, traduction de Moustapha Ndiaye.

- Kane, Ousmane (1989), “La confrérie ‘Tijaniyya Ibrahimiyya’ de Kano et ses liens avec la zawiya mère de Kaolack”, in Islam et sociétés au sud du Sahara, #4, pp. 27-40.

- Kane, Ousmane (1997), “Shaikh al-Islam Al-Hajj Ibrahim Niasse”, in Le temps des marabouts : Itinéraires et strategies islamiques en Afrique occidentale française v. 1880-1960, édité par David Robinson & Jean-Louis Triaud, Karthala, Paris, pp. 299-316.

- Kane, Ousmane & Leonardo Villalon (1995), “Entre confrérisme, réformisme et islamisme: les Mustarshidîn du Sénégal”, in Islam et sociétés au sud du Sahara, #9, pp. 119-201.

- Klein, Martin A. (1968), Islam and Imperialism in Senegal: Sine-Saloum 1847-1914, Stanford University Press.

- Loimeier, Roman (1994), “Cheikh Touré, du réformisme à l’islamisme: un Musulman sénégalais dans le siècle”, in Islam et sociétés au sud du Sahara, #8, pp. 55-66.

- Marone, Ibrahima (1970), “Le tidjanisme au Sénégal”, in Bulletin de l’IFAN, tome 32, série B, #1, pp. 136-215.

- Mbaye, El Hadji Ravane (1993), “La pensée et l’action d’El Hadji Malick Sy: un pôle d’attraction entre la shari‘a et la tariqa” (3 vols.), thèse de doctorat, Université Paris III-Sorbonne nouvelle. Compte-rendue de Jean-Louis Triaud in Islam et sociétés au sud du Sahara, 8, pp. 148-151.

- N’Gaïde, Abderrahmane (2002), “Les marabouts face à la ‘modernité’ : Le dental de Madina Gounass à l’épreuve”, in Le Sénégal contemporain, édité par Momar Coumba Diop, Karthala, Paris, pp. 617-652.

- Quadri, Y. A. (1985), “Ibrahim Niass (1902-1975): the Tijaniyyah Shaykh”, in Islam in the Modern Age, vol. 16, #2, pp. 109-120.

- Robinson, David (2000), Paths of Accommodation: Muslim Societies and French Colonial Authorities in Senegal and Mauritania, 1880-1920, Ohio University Press, Athens Ohio.

- Robinson, David (1993), “Malik Sy: un intellectuel dans l’ordre colonial au Sénégal”, in Islam et sociétés au sud du Sahara, #7, pp. 183-192.

- Samson, Fabienne (2005), Les marabouts de l’islam politique: Le Dahiratoul Moustarchidina Wal Moustarchidaty, un movement néo-confrérique sénégalais, Karthala, Paris.

- Seesemann, Rüdiger (2004), “The Shurafâ’ and the ‘Blacksmith’: The Role of the Idaw ‘Alî of Mauritania in the Career of the Senegalese Shaykh Ibrâhîm Niasse (1900-1975)”, in The Transmission of Learning in Islamic Afica, Scott S. Reese, editor, Brill, Leiden, pp. 72-98.

- Seesemann, Rüdiger and Benjamin F. Soares (2009), “’Being as Good Muslims as Frenchmen’: On Islam and Colonial Modernity in West Africa”, in Journal of Religion in Africa, vol. 39, pp. 91-120

- Van Hoven, Ed (1999), “Medina Gounass: The end of a Religious Isolate,” in ISIM Newsletter, #4, p. 25.

- Villalon, Leonardo A. (1995), Islamic Society and State Power in Senegal: Disciples and Citizens in Fatick, Cambridge University Press.

- Wane, Yaya (1974), “Ceerno Muhamadu Sayid Baa ou le soufisme intégral de Madina-Gunass”, in Cahiers d’études africaines, #56, pp. 671-698.